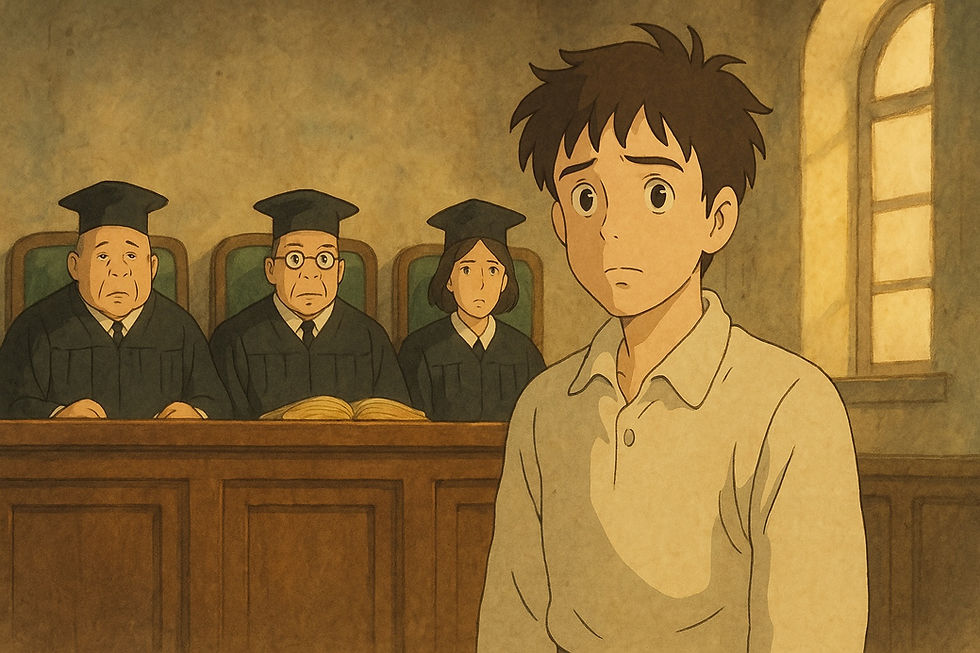

Justice Inverted, Innocence Endangered

- Jun 9

- 33 min read

Updated: Jun 16

A Critical Analysis of Justice, Guilt, and Innocence: Evaluating Claims of Systemic Inversion and the Presumption of Innocence

I. Introduction

This report undertakes a critical analysis of a series of deeply felt assertions regarding the state of contemporary justice systems. The core claims presented portray a system fundamentally inverted: where the guilty employ sophisticated manipulation to appear innocent and actively frame the truly innocent; where guilt itself has become a weapon wielded against the innocent, while innocence paradoxically serves the interests of the guilty; and where, consequently, the guilty evade punishment and are lauded, while the innocent bear the costs and societal condemnation. This perceived reality leads to the conclusion that justice has lost, or perhaps never possessed, its true meaning, worth, liability, and reliability, suggesting this inversion has become the prevailing norm. The text culminates in a radical proposal: that, until the justice system is fundamentally "fixed," all individuals should be universally considered innocent, regardless of accusation, as the only means to ensure security against the threats posed by the manipulative guilty.

The purpose of this critique is to provide an expert-level, multi-faceted evaluation of these claims. It will analyze the validity of the observations concerning manipulation and systemic inversion, assess the potential for hyperbole in the assertion that this represents the "norm," explore the underlying psychological and sociological mechanisms that might contribute to such phenomena, and critically examine the practicality and logical consistency of the proposed universal presumption of innocence. The analysis draws upon foundational legal principles, notably the presumption of innocence and its historical context including Blackstone's Ratio, philosophical conceptions of justice throughout history, empirical evidence from documented wrongful convictions and systemic failures, and relevant insights from psychology and sociology regarding manipulation, bias, and victim-blaming. The scope encompasses a systematic addressal of the eight specific points of critique requested, aiming for a rigorous, objective, and analytical assessment while remaining cognizant of the profound concerns about fairness and accountability that motivate the original text.

The report will proceed by first deconstructing the core claims regarding manipulation and the alleged inversion of guilt and innocence. It will then delve into the legal and philosophical principle of the presumption of innocence, comparing its ideal form with the author's interpretation of its current state. Subsequently, it will examine empirical evidence from wrongful convictions to assess how real-world failures support or contradict the text's generalizations. Psychological and sociological perspectives will be explored to understand potential mechanisms behind the described phenomena. The universality of the claims will be critically evaluated, seeking evidence of both systemic flaws and functioning justice. The proposed solution of universal innocence will be analyzed for its logical coherence and practical implications. The historical and philosophical evolution of the concept of justice will be investigated to address questions about its inherent meaning and reliability. Finally, the report will synthesize these findings into a comprehensive critique, evaluating the overall perspective offered on justice, guilt, and innocence.

II. Deconstructing the Core Claims: Manipulation, Inversion, and the Failure of Justice

The text presents a stark indictment of the justice system, built upon several interconnected claims about manipulation, the inversion of guilt and innocence, and a resulting systemic failure. A careful analysis of these assertions is necessary to evaluate their validity and potential basis in reality.

Claim 1: The Guilty Manipulate to Appear Innocent and Frame the Innocent

The assertion that guilty individuals actively manipulate the system not only to secure their own freedom but also to frame the innocent resonates strongly with documented failures within the criminal legal system. Research into wrongful convictions consistently identifies factors that can be indicative of, or exploited by, manipulation. Official misconduct by police or prosecutors, a disturbingly frequent factor, especially in serious cases like homicide, can involve deliberately hiding exculpatory evidence, coercing witnesses, or even fabricating evidence – actions that directly facilitate the framing of an innocent person. Similarly, perjury and false accusations, often stemming from witnesses or incentivized informants, are major contributors to wrongful convictions.

Psychological research provides frameworks for understanding the "unbelievable and unconceivable tactics" mentioned. Concepts like DARVO (Deny, Attack, Reverse Victim and Offender) describe a specific pattern where perpetrators, when confronted, deny the wrongdoing, attack the credibility of the accuser, and then claim victim status themselves, effectively flipping the narrative. This tactic aims explicitly to avoid responsibility and shift blame. Gaslighting, another manipulation technique, involves systematically undermining a victim's perception of reality, memory, or sanity through denial, distortion, and trivialization. This can erode a victim's self-trust, making them more vulnerable to further manipulation or even causing them to doubt their own innocence. While often discussed in interpersonal contexts like domestic abuse, these manipulative strategies can be deployed by defendants or their allies within the legal process, potentially influencing investigators, jurors, or public opinion. The documented effectiveness of DARVO in reducing victim believability and increasing victim blame in experimental settings suggests its potential potency within legal contexts.

The author's claim, therefore, aligns with both documented systemic failures (official misconduct, false accusations) and recognized psychological manipulation tactics (DARVO, gaslighting). Official misconduct can itself be a form of institutional manipulation, directly enabling the framing of the innocent, while individual perpetrators might employ psychological tactics to achieve similar ends by distorting perceptions and attacking credibility. There exists a plausible connection between the mechanisms of injustice observed in wrongful conviction cases and the manipulative behaviors described in psychological literature, lending credence to the idea that such framing, while perhaps not the norm, is a real and devastating possibility within the system.

Claim 2: Guilt as a Method Against Innocents / Innocence as a Pattern Favoring the Guilty

This claim posits a fundamental inversion of the justice system's intended dynamics. Ideally, the system is structured to protect the innocent, primarily through the presumption of innocence, which places the burden of proof squarely on the prosecution. This principle is explicitly designed to make conviction difficult, thereby favoring the accused to minimize the risk of punishing the innocent.

However, the text suggests this protective shield is being warped – that the concept of guilt is weaponized against those who are truly innocent, while the status of presumed innocence is exploited by the guilty. This perceived inversion can arise from systemic flaws. Cognitive biases among investigators, judges, and jurors – such as confirmation bias (seeking information that confirms initial suspicions) or fundamental attribution error (blaming character over circumstance) – can lead legal actors to wrongly perceive an innocent person as guilty, effectively using circumstantial evidence or ambiguous behavior as proof of guilt. Inadequate legal defense, often due to lack of resources, can leave innocent defendants unable to effectively counter the state's accusations or expose manipulation. Official misconduct, as discussed, can directly manufacture the appearance of guilt. Furthermore, the psychological phenomenon of victim blaming, where observers attribute responsibility to the victim for their own suffering (often rooted in a desire to believe the world is just or to feel less vulnerable oneself), can psychologically shift perceived guilt onto the innocent party. Conversely, sophisticated guilty parties might exploit these same systemic weaknesses – relying on procedural safeguards, inadequate investigation, or biased perceptions to escape accountability.

Claim 3: The Guilty Presented as Good Examples / The Innocent as Bad Examples

This assertion speaks to a breakdown in societal judgment and trust, potentially linked to the successful manipulation described earlier. When wrongful convictions occur, innocent individuals suffer devastating consequences, including loss of freedom, reputation, and years of life, effectively being presented as "bad examples" by the very system meant to protect them. Conversely, if guilty individuals successfully manipulate the system or benefit from its errors, they may evade consequences and maintain a facade of respectability, potentially being seen, erroneously, as "good examples" or victims of false accusation. Media narratives can play a significant role in shaping these public perceptions, sometimes creating a "court of public opinion" that presumes guilt before trial, making it harder for the legal presumption of innocence to hold sway. The success of DARVO tactics, for instance, relies on the perpetrator convincing observers that they are the actual victim.

Claim 4: Justice Has Lost Meaning/Worth/Reliability, or Never Had It

This profound expression of disillusionment reflects a deep sense of betrayal by the justice system. It questions the very foundation of justice's value. Historical analysis reveals that the ideal of a perfectly fair and reliable justice system has likely always been aspirational rather than fully realized. Throughout history, criminal justice systems have faced critiques for corruption, brutality, bias (particularly racial bias), and inconsistency. The evolution of legal thought itself shows ongoing debate about what constitutes "justice". The contemporary shift in some critical discourse from labeling the system a "criminal justice system" to a "criminal legal system" explicitly reflects this skepticism, questioning whether the apparatus inherently delivers justice or merely enforces law, sometimes unjustly. Therefore, the feeling that justice has lost its reliability, or the questioning of whether it ever truly possessed it, is not without historical and critical precedent. The gap between the system's stated ideals (fairness, impartiality, presumption of innocence) and the documented realities of error, misconduct, and bias fuels this profound disillusionment and leads individuals to question its fundamental worth.

Claim 5: This Inversion is the "Norm"

While the preceding analysis validates the existence of the phenomena described – manipulation, framing, systemic failures leading to unjust outcomes – the claim that this inversion represents the "norm" requires critical evaluation. The documented number of exonerations, while tragically high and representing immense suffering, must be considered against the backdrop of the millions of criminal cases processed annually by the US legal system. While precise conviction statistics are complex and varied across jurisdictions, the sheer volume suggests that known wrongful convictions, however devastating, constitute a fraction of total outcomes. Asserting that the guilty always manipulate successfully and the innocent always pay the price paints an overly simplistic and likely inaccurate picture of the system's day-to-day functioning. Systemic flaws are undeniably present and serious, potentially indicating deep-seated issues rather than isolated incidents. However, labeling the complete inversion of justice as the absolute "norm" across all cases appears to be a hyperbolic statement, likely born from profound frustration with observed injustices. It powerfully conveys the severity of the problem but risks overgeneralization. The reality is likely more complex, involving both instances of justice served and instances of profound failure.

III. The Presumption of Innocence: Ideal vs. Reality

A central pillar supporting the critique presented in the author's text is the perceived failure or inversion of the presumption of innocence. Understanding this principle's definition, history, and practical application is crucial for evaluating these claims.

Definition and Legal Basis

The presumption of innocence is a cornerstone legal principle asserting that any individual accused of a crime is legally considered innocent until the prosecution proves their guilt beyond a reasonable doubt. This principle remains in effect throughout the legal proceedings. Its core function is to place the legal burden of proof entirely on the prosecution. The state must present compelling evidence establishing every element of the crime to the high standard of "beyond a reasonable doubt". If reasonable doubt persists after the presentation of evidence, the accused must be acquitted. The defendant bears no burden to prove their innocence; they do not have to testify, call witnesses, or present evidence, and choosing not to do so cannot be held against them.

While not explicitly enumerated in the text of the U.S. Constitution, the presumption of innocence is deeply embedded in the American legal system through statutes, historical court decisions (like Taylor v. Kentucky), and its connection to fundamental due process rights guaranteed by the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments. It is recognized internationally as a fundamental human right, enshrined in documents like the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (Article 11) and the European Convention on Human Rights (Article 6.2). It is considered a basic requirement for a fair trial.

Historical Context and Blackstone's Ratio

The roots of this principle extend deep into legal history. Roman law articulated the maxim "Ei incumbit probatio qui dicit, non qui negat" – proof lies on him who asserts, not on him who denies. Medieval canonical jurists like Jean Lemoine expressed the idea that "a person is presumed innocent until proven guilty". The principle became firmly established in English common law and was famously articulated by British barrister Sir William Garrow in the late 18th century as "presumed innocent until proven guilty," emphasizing the need to robustly test accusations in court.

This philosophy is powerfully encapsulated in Blackstone's Ratio, articulated by the preeminent English jurist William Blackstone: "better that ten guilty persons escape, than that one innocent suffer". This ratio signifies a deliberate moral and legal choice to prioritize the protection of innocence above the certainty of punishing all guilt. It acknowledges the fallibility of human judgment and dictates that the system should err on the side of caution to avoid the profound injustice of convicting an innocent person. Variations of this sentiment exist, with figures like Benjamin Franklin suggesting a 100:1 ratio and Maimonides advocating 1000:1, indicating an even stronger emphasis on protecting the innocent. Blackstone's principle profoundly influenced the development of the high "beyond a reasonable doubt" standard of proof in criminal trials, reflecting a quantifiable preference for minimizing wrongful convictions (Type 1 errors) even at the cost of potentially increasing wrongful acquittals (Type 2 errors). This ratio represents a probabilistic and ethical calculation about which type of error society finds more tolerable.

Author's Interpretation vs. Legal Reality

The author's text claims, "Innocence has become a pattern in favor of the guilty." This statement appears to misinterpret or invert the intended function of the presumption of innocence. The principle is designed to favor the accused (who is presumed innocent) precisely to protect against wrongful conviction. The difficulty in meeting the "beyond a reasonable doubt" standard is a feature, not a bug, reflecting the values embedded in Blackstone's Ratio.

However, the author's underlying critique may be directed not at the principle itself, but at its application and effectiveness in the current system. They perceive that this protective principle is being exploited by the truly guilty or failing to adequately shield the truly innocent. There are indeed real-world challenges to the presumption's effectiveness. The pervasive influence of media can create a strong public perception of guilt before a trial even begins, potentially biasing jurors or influencing legal proceedings. Decisions regarding bail can result in pretrial detention, limiting an individual's liberty despite the legal presumption of innocence, although such decisions are meant to be based on risk assessments rather than punishment. The sheer difficulty of overcoming societal condemnation once accused, regardless of the legal standard, poses a practical challenge. This tension between the formal legal presumption of innocence and the often-operative socio-psychological presumption of guilt creates a significant vulnerability. Legal safeguards enshrined in procedure may struggle to counteract powerful extra-legal narratives, ingrained cognitive biases among legal actors, or the weight of public opinion, potentially weakening the practical protection the presumption is intended to afford.

Exceptions and Limitations

It is also important to note that the presumption is not absolute. There are established legal exceptions where the burden of proof (or at least an evidential burden) can shift to the accused, such as in the defense of insanity or under specific statutory provisions (statutory reversals). Furthermore, as mentioned, the presumption does not guarantee freedom before trial; individuals can be detained under certain circumstances. There are also ongoing scholarly debates about whether the presumption should be understood purely procedurally (affecting only the trial process) or also substantively (influencing the definition of criminal offenses).

The author's critique, therefore, touches upon a complex reality where a fundamental legal principle designed to protect the innocent faces significant practical challenges and potential manipulations. While the principle itself aims to prevent the conviction of the innocent, even at the cost of letting some guilty go free, the author perceives a system where this balance is broken – where the innocent are frequently condemned, and the guilty exploit the system's safeguards. This suggests a perceived failure in the implementation of the principle and a breakdown in the moral calculus that Blackstone's Ratio represents, where the system seems prone to making the very errors it was designed to prevent, potentially due to active manipulation rather than mere chance.

IV. Wrongful Convictions: Evidence of Systemic Flaws?

The phenomenon of wrongful convictions provides crucial empirical data for evaluating the author's claims about innocent individuals suffering while the guilty potentially evade justice. The existence of exonerations demonstrates that the system is fallible and capable of producing profoundly unjust outcomes.

Prevalence and Scale

Data compiled by organizations like the National Registry of Exonerations (NRE) documents thousands of cases where individuals convicted of crimes were later officially cleared based on new evidence of innocence. As of early 2024, the NRE had recorded over 3,478 exonerations in the United States since 1989, with similar figures cited by other sources. In 2023 alone, 153 exonerations were recorded. The human cost is staggering; these exonerated individuals collectively spent tens of thousands of years wrongly incarcerated. Those exonerated in 2023 lost an average of 14.6 years each, totaling 2,230 years for that cohort alone. Innocence Project clients, a subset of all exonerees, collectively lost over 4,000 years.

Crucially, these documented exonerations are widely believed to represent only a fraction of the actual number of innocent people imprisoned. Carrying out an exoneration is a lengthy and resource-intensive process. Statistical estimates suggest that the rate of wrongful conviction in serious criminal cases could be significant, potentially around 6% or even higher. Given the large incarcerated population in the U.S., this implies that tens, if not hundreds, of thousands of innocent individuals may currently be imprisoned. This data lends significant weight to the author's assertion that innocent people are suffering within the system.

Key Causes of Wrongful Convictions

Research based on exoneration cases has identified recurring patterns and factors that contribute to these miscarriages of justice. These are not isolated incidents but point towards potential systemic vulnerabilities:

Official Misconduct: This is a leading cause, particularly in the most serious cases. In 2023, official misconduct by police, prosecutors, or other officials was present in at least 77% (118 out of 153) of all exonerations and a striking 85% of homicide exonerations. Misconduct includes concealing evidence favorable to the defense (Brady violations), coercing witnesses or defendants, fabricating evidence, and knowingly presenting false testimony. This directly supports the possibility of active manipulation and framing by state actors.

Eyewitness Misidentification: This remains the single greatest cause of wrongful convictions overturned by DNA testing, playing a role in roughly 63-72% of such cases. Human memory is fallible and susceptible to contamination. Factors like stress during the crime, cross-racial identification difficulties, and suggestive lineup or photo array procedures employed by police contribute significantly to errors.

Perjury or False Accusation: False testimony from witnesses, including incentivized jailhouse informants ("snitches"), is another major factor, present in a large majority of exonerations (116 out of 153 in 2023).

False Confessions: Despite seeming counterintuitive, a significant percentage of innocent individuals (around 12-30% in various studies) confess to crimes they did not commit. This often results from lengthy, coercive, or manipulative interrogation techniques employed by law enforcement, particularly affecting vulnerable individuals like youth or those with intellectual disabilities.

False or Misleading Forensic Evidence: This involves both the use of discredited "junk science" techniques (like bite mark analysis or hair microscopy) that lack rigorous scientific validation, and the misapplication, misinterpretation, or even fabrication of results from scientifically valid methods (like DNA analysis or serology). It was a factor in 24-52% of cases depending on the dataset studied.

Inadequate Legal Defense: The Sixth Amendment guarantees the right to counsel, but the reality often falls short. Overworked, underfunded, or incompetent defense attorneys failing to investigate adequately, call crucial witnesses, consult experts, or effectively challenge the prosecution's case are a significant contributing factor.

The following table summarizes these key factors based on available data:

Factor | Estimated Prevalence | Key Examples/Mechanisms |

|---|---|---|

Official Misconduct | ~77% of 2023 NRE cases; 85% of 2023 homicide cases | Hiding exculpatory evidence, coercing witnesses/confessions, fabricating evidence, suggestive ID procedures, false testimony |

Eyewitness Misidentification | ~63-72% of DNA exonerations; 28-50% of NRE/IP cases | Memory fallibility, stress, cross-racial ID issues, suggestive police procedures |

Perjury/False Accusation | ~76% of 2023 NRE cases; ~18-19% of DNA/IP exonerations | Lies by civilian witnesses, incentivized jailhouse informants ("snitches") |

False Confessions | ~12-30% of DNA/IP/NRE cases | Coercive interrogation, intimidation, psychological pressure, deception by police, youth/disability vulnerability |

Flawed Forensic Science | ~24-53% of NRE/IP cases | Use of unvalidated techniques (bite marks, hair microscopy), errors in valid tests, misinterpretation, fabrication |

Inadequate Legal Defense | Prevalence varies (59/153 in 2023 NRE); Often co-occurs | Lack of investigation, failure to call witnesses/experts, insufficient resources, ineffective cross-examination |

Racial Disparities | ~84% of 2023 NRE exonerees were POC; ~57% of IP clients Black | Black individuals disproportionately represented among exonerees, especially for murder/sexual assault |

(Note: Prevalence percentages vary depending on the dataset (e.g., NRE overall vs. Innocence Project DNA cases) and year. Sources often report slightly different figures based on their specific case sets and definitions.)

Racial Disparities

The data consistently reveals stark racial disparities. People of color, particularly Black individuals, are vastly overrepresented among the exonerated compared to their proportion in the general population. In 2023, nearly 84% of exonerees were people of color, with 61% being Black. Studies suggest innocent Black individuals are significantly more likely to be convicted of crimes like murder and sexual assault than innocent white individuals. This aligns with historical and ongoing critiques of systemic racism within the criminal legal system.

Relationship to author's Claims

This body of evidence provides strong support for several aspects of the author's claims. It unequivocally demonstrates that innocent individuals suffer immensely due to system failures. The recurring nature of these causes points towards systemic issues rather than just random errors. The high prevalence of official misconduct directly supports the possibility of manipulation and framing originating from within the system itself.

However, the data primarily focuses on the causes of wrongful convictions, identifying the errors and misconduct that led to the innocent being punished. It doesn't necessarily provide direct evidence that the truly guilty parties are always the primary actors orchestrating the framing in these specific exoneration cases, although they undoubtedly benefit when an innocent person is convicted in their place. The data highlights system failures that allow injustice to occur, which can be exploited by the guilty or arise from negligence, bias, or misconduct by state actors.

Furthermore, the identified causes of wrongful conviction are often interconnected. For instance, inadequate defense counsel may fail to challenge faulty eyewitness testimony or expose official misconduct. Coercive interrogation tactics (misconduct) can directly lead to false confessions. This interconnectedness suggests a systemic fragility where a failure in one component can enable or exacerbate failures in others, creating pathways for the kind of complete inversion of justice the author describes. The high rate of official misconduct, especially in the most serious cases, indicates that in a significant number of documented wrongful convictions, the injustice stemmed from intentional wrongdoing by state actors, lending credence to the author's concern that the system itself can be a source of manipulation and injustice.

V. Psychological and Sociological Dimensions

Understanding the psychological and sociological factors at play can illuminate the mechanisms behind the manipulation, blame-shifting, and systemic errors described in the author's text. Concepts such as DARVO, gaslighting, cognitive bias, and victim blaming offer valuable frameworks.

Manipulation Tactics: DARVO and Gaslighting

Perpetrators seeking to evade accountability may employ specific psychological manipulation tactics.

DARVO (Deny, Attack, Reverse Victim and Offender): This acronym describes a common reaction pattern observed in perpetrators, particularly those accused of abuse or sexual offenses, when confronted. The perpetrator first Denies the harmful behavior occurred. When presented with evidence, they Attack the person confronting them (the victim, whistleblower, or concerned party), often targeting their credibility, character, or motives. Finally, they Reverse Victim and Offender, positioning themselves as the actual victim (e.g., of false accusations, misunderstanding, or the confrontation itself) and portraying the true victim as the aggressor or liar. This strategy aims to deflect responsibility, silence critics, shift blame, and manipulate observers' perceptions. Research suggests DARVO is effective in making observers view perpetrators as less responsible and victims as more responsible for the harm. It can manifest institutionally ("Institutional DARVO," where an organization denies wrongdoing, attacks the whistleblower, and claims victim status) and legally ("Legal DARVO," where perpetrators file retaliatory lawsuits, like defamation cases, against their accusers). This provides a concrete psychological mechanism for the "unbelievable and unconceivable tactics" the author alleges guilty parties use to frame the innocent and present themselves as victims.

Gaslighting: This is a form of psychological manipulation where the perpetrator aims to make the victim doubt their own memory, perception, judgment, or sanity. Tactics include persistent denial of events ("That never happened"), distortion of facts, trivializing the victim's feelings ("You're too sensitive"), withholding information, blame-shifting, projection (accusing the victim of the perpetrator's own behavior), and using confusing or irrelevant language ("word salad") to derail conversations. Gaslighting often occurs in relationships with power imbalances, such as domestic violence, and can be used to control the victim by eroding their self-trust. It can make victims more susceptible to DARVO tactics and has been identified as a factor in coercing victims to recant testimony. Gaslighting explains how a victim might come to doubt their own innocence or experiences, or how observers might be convinced to disregard the victim's account.

Cognitive Biases in Legal Actors

The justice system relies on human judgment, which is susceptible to cognitive biases – unconscious mental shortcuts or tendencies that can systematically distort perception, memory, and decision-making. These biases are universal and generally operate outside conscious awareness.

Impact on Jurors and Judges: Research confirms that both jurors and judges are vulnerable to cognitive biases despite legal training. Common biases include:

Confirmation Bias: The tendency to seek out, interpret, favor, and recall information that confirms pre-existing beliefs or hypotheses, while ignoring or downplaying contradictory evidence. This is particularly potent in legal settings, where initial impressions of guilt or innocence, perhaps formed through pre-trial publicity or stereotypes, can lead jurors or judges to selectively evaluate evidence presented during the trial.

Availability Heuristic: Judging the likelihood of an event based on how easily examples come to mind. Vivid or recent information might be given undue weight.

Anchoring Bias: Over-relying on the first piece of information encountered.

Hindsight Bias: The tendency to see past events as having been more predictable than they actually were.

Framing Effects: How information is presented can influence decisions.

Crime-Type Bias: Perceived strength of a case influenced by the severity of the crime, potentially linked to social cognition processes like mentalizing or implicit bias.

Bounded Rationality: Decision-making is limited by available information, cognitive capacity, and time, leading to reliance on heuristics and "satisficing" rather than optimal decisions.

Impact on Investigators: Law enforcement personnel are also susceptible. Confirmation bias can lead investigators to "tunnel vision," focusing prematurely on a single suspect and interpreting all subsequent evidence through the lens of that suspect's guilt, while disregarding information pointing elsewhere. The cases of Levon Brooks and Kennedy Brewer, wrongly convicted in similar Mississippi cases based on flawed bite mark evidence while evidence pointing to the real perpetrator was overlooked, exemplify this danger. The fundamental attribution error – attributing behavior to inherent character traits rather than situational factors – can also lead investigators to misinterpret ambiguous actions as signs of guilt.

These cognitive biases provide a crucial mechanism explaining how the system can fail even without deliberate malice. They show how investigators might wrongly target an innocent person, how prosecutors might build a weak case based on biased interpretations, and how judges or jurors might misinterpret evidence or fail to see through manipulation, thereby contributing to wrongful convictions and allowing the guilty to escape.

Victim Blaming

Victim blaming occurs when observers hold victims partially or fully responsible for the harm they have experienced. This tendency has psychological roots:

Just World Hypothesis: The belief that the world is fundamentally just and people get what they deserve. To maintain this belief when confronted with undeserved suffering, observers may unconsciously rationalize the event by blaming the victim's actions or character, thereby preserving their sense of a predictable and fair world.

Attribution Error: The tendency to attribute others' misfortunes to their internal characteristics (e.g., carelessness, poor judgment) while attributing our own successes to external factors and failures to situational ones.

Invulnerability Theory / Defensive Attribution: Blaming the victim can create a false sense of security for the observer ("That wouldn't happen to me because I wouldn't have acted that way"), distancing them from the threatening possibility of random victimization.

Factors influencing victim blaming include the type of crime (though research is mixed, particularly comparing rape and robbery), the victim's behavior (e.g., perceived risk-taking, level of resistance), the relationship between victim and perpetrator (acquaintance rape victims sometimes blamed more), characteristics of the victim (e.g., gender, adherence to traditional roles, perceived promiscuity), and characteristics of the observer (e.g., gender, sexist attitudes, belief in rape myths, belief in a just world). Victim blaming has severe consequences, increasing victim distress and deterring reporting of crimes.

Victim blaming provides a psychological pathway for the inversion the author describes. It explains how societal attitudes or biases within the legal system might wrongly shift responsibility onto the innocent victim, facilitating the guilty party's narrative and escape from accountability. It can also contribute to victims internalizing blame, potentially aligning with the author's claim that "innocents believe they are guilty."

These psychological and sociological factors do not operate in isolation. There is a potential synergy where individual manipulation tactics employed by perpetrators (DARVO, gaslighting) can effectively exploit systemic vulnerabilities like cognitive biases among legal actors and societal tendencies toward victim blaming. A perpetrator's narrative that denies responsibility and attacks the victim's credibility might find fertile ground in an investigator already prone to confirmation bias or jurors influenced by just-world beliefs. This interaction can amplify the likelihood of an unjust outcome. Furthermore, the concept of "Institutional DARVO", where the system itself engages in denial, attacks the victim/whistleblower, and reverses roles (e.g., prosecuting victims for false reporting), offers a powerful lens for understanding the author's most severe claims of systemic inversion. It suggests that the system, in some instances, may actively replicate the manipulative behaviors of abusers, leading to the perception of a fundamentally corrupted process.

VI. Universality of Failure vs. Functioning Justice

The author's text strongly implies that the described inversion of justice – where the guilty manipulate the system to frame the innocent – is not merely an occasional aberration but has become "the norm." Critically evaluating this claim requires balancing the undeniable evidence of serious systemic flaws against the sheer scale and complexity of the criminal legal system and evidence suggesting it does function, albeit imperfectly, in many instances.

Acknowledging Systemic Flaws

As established in Section IV, the evidence of wrongful convictions is substantial and deeply troubling. The recurring causes – official misconduct, eyewitness error, false confessions, flawed science, inadequate defense, perjury – point to systemic vulnerabilities rather than isolated mistakes. The disproportionate impact on people of color highlights embedded biases. Historical analyses further confirm that U.S. criminal justice systems have long grappled with issues of unreliability, corruption, brutality, and discrimination, lending credence to the idea that achieving true justice has been an ongoing struggle. The critique embedded in the term "criminal legal system" versus "criminal justice system" captures this deep-seated skepticism about the system's inherent fairness. The author's concerns are therefore rooted in demonstrable problems.

Counter-Evidence and Nuance

However, asserting that this failure is the universal "norm" overlooks several key factors:

Scale of the System: Annually, law enforcement agencies in the U.S. handle millions of reported offenses, and courts process vast numbers of criminal cases. While precise national conviction data is difficult to aggregate consistently across all jurisdictions and offense types, the number of documented exonerations (in the thousands over decades) represents a small fraction of the total cases processed. While even one wrongful conviction is unacceptable, and the true number is likely much higher than those exonerated, the available data does not support the conclusion that most or all outcomes reflect the inversion described.

Crime Rates and Clearance Rates: While crime rates fluctuate and public perception may differ, official statistics from both the FBI (based on police reports) and the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS, based on victim surveys) show significant long-term declines in both violent and property crime rates since the early 1990s. This suggests some level of effectiveness in crime control or prevention, though it doesn't speak directly to the accuracy of individual convictions. Furthermore, while police clearance rates (the percentage of reported crimes resulting in an arrest or other resolution) have declined for many offenses and remain low for property crimes, they are not zero. In 2022, police cleared over half of reported murders and non-negligent manslaughters and over 40% of aggravated assaults. This indicates successful investigation and identification of perpetrators in a substantial portion of serious violent crimes.

Functioning Elements and Reform Efforts: The existence and work of Conviction Integrity Units (CIUs) within prosecutors' offices and independent Innocence Organizations demonstrate mechanisms within or alongside the system aimed at identifying and correcting errors. While the effectiveness and prevalence of CIUs vary, their existence signifies an acknowledgment of fallibility and an attempt at self-correction. Foundational legal principles like the presumption of innocence and due process requirements, however imperfectly applied, still provide the framework for criminal procedure. Moreover, research identifying causes of wrongful conviction (e.g., problematic eyewitness ID procedures) has led to reforms in some jurisdictions, indicating a capacity for improvement based on evidence. This suggests an ongoing tension between forces perpetuating injustice and those seeking to rectify it, contradicting a narrative of monolithic, uniform failure.

Focus on Failures: Data sources like the NRE are, by definition, registries of failure. They are essential for understanding what goes wrong, but they do not provide a representative sample of all criminal case outcomes. Focusing solely on exonerations can create a perception skewed towards failure, potentially influenced by the availability heuristic – dramatic cases of injustice are more memorable and reported than routine cases that may have reached a correct outcome.

Evaluating "The Norm"

Considering this evidence, the claim that the manipulation and inversion described constitute the "norm" appears to be an overstatement. The identified failures are undeniably serious, frequent enough to indicate systemic problems rather than mere anomalies, and demand urgent, comprehensive reform. However, the available data does not support the conclusion that every, or even most, interactions with the criminal legal system result in the guilty framing the innocent. The author's language functions as powerful rhetoric, effectively conveying the profound sense of injustice and betrayal engendered by wrongful convictions and systemic biases. It highlights the devastating reality that the system can operate in this inverted manner. Yet, taken as a literal description of the system's typical functioning across its vast scope, it likely represents hyperbole. The reality is more likely a complex mix of cases resolved justly, cases resulting in error due to negligence or bias, and cases involving deliberate manipulation, with the precise proportions remaining difficult to ascertain.

VII. Striving for a More Perfect Justice: Pathways to Systemic Improvement

The assertion that "all humans [should be considered] as innocents until justice is fixed" stems from a profound disillusionment with systemic flaws. However, this proposal, while highlighting the urgency of reform, rests on the premise of achieving a "perfect" system, an ideal that is likely unattainable in a constantly evolving world. No human system, especially one as complex as the administration of justice, can be entirely free of error or immune to manipulation. The more pragmatic and constructive approach lies not in awaiting an abstract state of perfection, but in relentlessly striving to approach a more perfect system by identifying and addressing its inherent flaws. This section will hypothesize on possibilities for mitigating these flaws, with a particular focus on reducing human error and enhancing the integrity of evidence through systemic reforms and technological advancements.

Systemic and Procedural Reforms: Addressing Foundational Flaws

Many identified flaws in the justice system are deeply embedded in its procedures and statutory frameworks. Evidence-based reforms aimed at increasing fairness, judicial discretion, and opportunities for rehabilitation offer pathways to improvement:

Sentencing and Parole Reform:

Eliminating Mandatory Minimum Sentences: Mandatory minimums are criticized for driving mass incarceration, stripping judges of discretion, and giving prosecutors excessive leverage in plea negotiations. Repealing such laws, like the proposed Marvin Mayfield Act in New York, would allow judges to consider individual circumstances, such as age, trauma history, and disabilities, leading to more tailored and potentially just sentences.

Expanding "Second Look" Mechanisms: Laws like the Second Look Act would permit judicial review and reconsideration of lengthy sentences after a significant portion has been served, especially for those sentenced young or who have demonstrated substantial transformation. This acknowledges that individuals can change and that societal views on appropriate punishment evolve. Compassionate release programs, especially when broadened, can also function as a form of "second look," allowing for release based on extraordinary and compelling circumstances, including excessive original sentences or significant rehabilitation.

Reforming Parole Standards: Legislation like Elder Parole (allowing parole review for older, long-serving individuals) and Fair and Timely Parole (focusing on rehabilitation and current risk rather than solely the original crime) aim to make the parole process more equitable and reflective of an individual's current status. Recidivism rates for older individuals are notably lower, making continued incarceration less justifiable from a public safety perspective and more costly.

Enhancing Alternatives to Incarceration:

Expanding Treatment Courts: For crimes stemming from issues like substance abuse or mental illness, expanding access to treatment-based alternatives to incarceration is crucial. Initiatives like the Treatment Court Expansion Act aim to modernize diversion programs, making them accessible to a wider range of individuals with "functional impairments" and shifting towards evidence-based, pre-plea models where appropriate. This recognizes that incarceration often exacerbates underlying issues rather than resolving them.

Leveraging Technology to Mitigate Human Error and Bolster Evidence Integrity

Human error, cognitive bias, and even intentional misconduct are significant contributors to miscarriages of justice. While technology is not a panacea, its thoughtful application can help reduce these factors and enhance the reliability of evidence.

Objective Evidence Collection and Management:

Body-Worn Cameras (BWCs): BWCs provide objective, contemporaneous recordings of police-citizen interactions. This footage can be invaluable in corroborating or refuting accounts of events, thereby aiding in the resolution of misconduct claims and potentially deterring misconduct itself due to the awareness of being recorded. BWCs enhance transparency and can help build community trust. However, policies regarding their use, data storage, access, and privacy implications must be carefully managed.

Blockchain for Chain of Custody: Blockchain technology offers a method for creating immutable, time-stamped records of forensic evidence. This can establish a clear and tamper-proof chain of custody, enhancing the integrity and admissibility of digital and physical evidence.

Advanced Forensic Analysis and Presentation:

AI in Forensic Science: Artificial intelligence is increasingly used in analyzing complex forensic data. Applications include DNA and genetic forensic analysis (such as haplogroup analysis and STR profile analysis), pattern recognition, crime scene reconstruction, digital forensics, and even biomechanical analysis from limited inputs like surveillance footage. AI can process vast datasets, identify patterns humans might miss, and automate tasks, potentially reducing human error and speeding up investigations.

Virtual Reality (VR) in the Courtroom: VR technology can create immersive reconstructions of crime scenes or accidents, allowing jurors to "experience" the environment from specific perspectives. This can enhance understanding of complex spatial evidence, improve memory retention of critical details, and potentially lead to fairer verdicts compared to relying solely on photographs or 2D diagrams. However, the cost of VR and concerns about potential bias in how VR experiences are created and perceived need to be addressed.

The Double-Edged Sword of AI: Navigating Potential and Pitfalls

Artificial intelligence holds significant promise for improving efficiency and even accuracy in the justice system, but its deployment is fraught with ethical challenges, particularly concerning bias.

Potential Benefits: AI can enhance court efficiency by automating case management tasks and assisting in judicial deliberation, for example, by predicting recidivism (though this is a contentious application). In investigations, AI can analyze massive datasets to identify suspects or patterns that human analysts might miss.

The Critical Issue of Algorithmic Bias: A major concern is that AI systems, trained on historical data, can inherit and amplify existing societal and systemic biases, particularly racial biases. Predictive policing algorithms, for instance, may disproportionately target minority communities if based on biased historical arrest data, creating a feedback loop of over-policing. Risk assessment tools used in pretrial decisions have also shown tendencies to assign higher risk scores to minority defendants under similar circumstances. Studies by NIST have shown US-developed facial recognition algorithms misidentifying Asian and African Americans at significantly higher rates than Caucasians.

Need for Transparency, Oversight, and Ethical Guidelines: To harness AI's benefits while mitigating its risks, robust frameworks for transparency, accountability, and ethical oversight are essential. This includes understanding how AI tools arrive at their conclusions, ensuring data inputs are as unbiased as possible, and providing comprehensive training for legal professionals on the effective and ethical use of AI. The fragmented nature of current AI regulation highlights the need for more cohesive standards.

The Ongoing Pursuit of a More Just System

The path to a more just system is not through a wholesale declaration of universal innocence pending an unattainable state of perfection, but through diligent, ongoing reform. Addressing systemic procedural flaws by restoring judicial discretion, expanding rehabilitative alternatives, and ensuring fairer sentencing and parole mechanisms is fundamental. Concurrently, the careful and ethical integration of technologies like BWCs, blockchain, advanced forensic AI, and VR can help mitigate human error, enhance evidence integrity, and improve understanding in legal proceedings. However, the introduction of new technologies, especially AI, must be approached with caution, acknowledging and actively working to counteract inherent biases and ensure that these tools serve justice rather than perpetuate existing inequities. Ultimately, the pursuit of a "more perfect" justice system requires a sustained commitment to evidence-based practices, continuous evaluation of reforms and technologies, and an unwavering focus on fairness, accountability, and the protection of individual rights.

VIII. The Evolving Concept of Justice

The author's text fundamentally questions the nature and reliability of justice, asking whether it has lost its meaning or, perhaps, never truly possessed it. Addressing this requires exploring the historical and philosophical basis of the concept, acknowledging its contested nature, and examining how its perceived worth and reliability have evolved over time.

Historical and Philosophical Basis

The quest to define and achieve justice is ancient and central to Western thought. A common thread, traceable back to Roman law codified in the Institutes of Justinian, defines justice as "the constant and perpetual will to render to each his due". This core idea of giving individuals what they are owed permeates much of the philosophical tradition, though what is considered "due" has been the subject of extensive debate.

Ancient Greece: Plato conceived of justice primarily as a virtue of rational order and harmony, both within the individual soul and the structure of the ideal state, where each part performs its proper function. Aristotle provided a more practical framework, defining justice as encompassing both what is lawful and what is fair. He famously distinguished between distributive justice (concerning the fair, often proportional, allocation of goods and honors among members of a community) and corrective justice (rectifying imbalances caused by wrongful actions between individuals).

Medieval Christianity: Thinkers like Augustine and Aquinas integrated classical ideas with theological frameworks. Justice remained the virtue of giving each their due, but this was grounded in God's eternal law and natural law. Aquinas elaborated on Aristotelian distinctions, emphasizing proportional distribution and fairness in transactions, viewing justice as a rational mean.

Early Modernity: The Enlightenment saw shifts towards secular and social contract theories. Thomas Hobbes viewed justice not as a natural virtue but as an "artificial" one, arising from the social contract and consisting simply in the keeping of covenants enforced by a sovereign. David Hume argued that justice originates solely from considerations of public utility, primarily serving to protect property rights and maintain social order, deeming strict equality impractical.

Recent Modernity: Immanuel Kant grounded justice in reason and respect for individual autonomy and freedom. His universal principle required that actions be permissible only if they could coexist with the freedom of everyone else according to a universal law. John Stuart Mill, a utilitarian, defined justice as a name for certain essential social utilities, particularly those protecting crucial moral rights and maximizing overall happiness or liberty.

Contemporary Thought: John Rawls's influential theory of "justice as fairness" proposed principles that free and equal persons would choose in a hypothetical "original position" behind a "veil of ignorance". These principles prioritize equal basic liberties for all and permit social and economic inequalities only if they benefit the least advantaged (the difference principle) and are attached to positions open to all under fair equality of opportunity. Rawls also emphasized the concept of legitimacy in a pluralistic society, arguing that political power is properly exercised only according to a constitution whose essentials all citizens could reasonably endorse.

The Contested Nature of Justice

This brief overview demonstrates that the meaning, scope, criteria, and application of justice have always been contested. Philosophers continue to debate fundamental distinctions:

Is justice primarily about upholding existing laws and norms (conservative justice) or about achieving an ideal standard based on principles like equality or desert (ideal justice)?

What is the relationship between corrective justice (righting wrongs) and distributive justice (fair allocation)?

Is justice achieved through fair procedures or determined by the fairness of the substantive outcome?

Is what is due to a person determined comparatively (in relation to others) or non-comparatively (based on their individual situation)?

What is the scope of justice? Does it apply only to humans, or also to animals? Does it apply primarily within specific relationships (like citizenship) or universally? Is it primarily a virtue of institutions or also of individuals in their daily lives? Should it focus solely on the redistribution of material goods, or also encompass issues of recognition and status?

Reliability and Worth Over Time

Given this history of evolving definitions and persistent debate, the author's question – "Justice has lost its true meaning... Or it never had any...?" – takes on significant weight. The historical record of criminal justice systems clearly shows periods where practice fell far short of any reasonable ideal, marked by corruption, brutality, inefficiency, and profound bias. The reliability and fairness of these systems have fluctuated, subject to social pressures, political influences, and inadequate resources.

Therefore, it can be argued that there never was a single, universally accepted "true meaning" of justice that was perfectly realized in practice. The "worth" of justice, perhaps, lies not in a mythical golden age of perfect implementation, but in its enduring power as a critical ideal and an aspiration. It provides the standard against which social arrangements and legal systems are measured, critiqued, and reformed. The disillusionment expressed in the author's text, while deeply pessimistic, is part of this long historical tradition of critiquing the gap between the ideal of justice and its flawed reality. The questioning of whether the system truly achieves "justice" is mirrored in contemporary critical discourse, exemplified by the deliberate use of the term "criminal legal system" instead of "criminal justice system". This terminological choice emphasizes the system's function as a state apparatus enforcing laws, deliberately withholding the aspirational label "justice" due to concerns about its historical and ongoing failures to deliver fairness and equity, particularly concerning race and poverty. This resonates strongly with the author's skepticism about the system's fundamental nature and reliability.

IX. Synthesis and Conclusion

This critique has examined a series of claims portraying a justice system fundamentally inverted, where the guilty manipulate outcomes to the detriment of the innocent, leading to a loss of faith in justice itself and culminating in a proposal for universal innocence until the system is reformed. The analysis, drawing on legal principles, philosophical history, empirical data, and psychological insights, yields several key conclusions.

Summary of Findings

Validity of Observations: The core concerns expressed in the text are grounded in demonstrable realities. Wrongful convictions occur with disturbing frequency, resulting in devastating consequences for the innocent. Systemic flaws, including official misconduct, eyewitness error, false confessions, flawed forensic science, inadequate defense, and perjury, are well-documented causes. Psychological manipulation tactics like DARVO and gaslighting offer plausible mechanisms for how perpetrators might actively distort perceptions and evade accountability. Cognitive biases can lead well-intentioned legal actors to make critical errors, and societal tendencies toward victim blaming can further disadvantage the innocent. Historical and ongoing critiques highlight the justice system's persistent struggles with reliability, fairness, and bias, particularly racial bias. The author's observations about the potential for injustice and manipulation within the system are thus validated by substantial evidence.

Strength of Arguments and Hyperbole: While the underlying issues are real and severe, the assertion that the described inversion – guilty framing the innocent, innocence favoring the guilty – represents the universal "norm" appears hyperbolic. The scale of the criminal legal system suggests that documented exonerations, while critically important, represent a fraction of total case outcomes. Evidence of functioning aspects, such as crime clearance (however imperfect) and internal reform efforts (CIUs, Innocence Projects), complicates a narrative of total systemic failure. The author's rhetoric powerfully conveys the gravity of the system's failings but likely overgeneralizes these failures to encompass the entirety of the system's operation.

Proposed Solution: The proposal to "consider all humans as innocents" until justice is "fixed" is logically inconsistent and practically unworkable. It undermines the very concept of justice by eliminating the necessary distinctions between guilt and innocence and removing mechanisms for accountability and victim protection. While unfeasible as policy, it serves as a potent expression of profound disillusionment with the current state of affairs and an extreme prioritization of protecting the innocent, illustrating the endpoint of Blackstone's Ratio when taken to its absolute limit. Its impracticality underscores the necessity of focusing on concrete reforms rather than abandoning the pursuit of justice altogether.

Overall Perspective: The text offers a deeply critical perspective, highlighting the painful gap between the ideals of justice (fairness, reliability, protection of innocence) and its often-flawed reality. It correctly identifies that manipulation by guilty parties can occur, exploiting both individual psychology and systemic weaknesses. It rightly points to the immense suffering caused by system failures. While potentially overly pessimistic in its generalization, the perspective serves as a stark reminder of the stakes involved in the administration of criminal law and the urgent need for vigilance against injustice.

Nuanced Conclusions

The criminal legal system is neither the perfectly objective arbiter of truth idealized in theory, nor the universally corrupt and inverted machine depicted in the author's most sweeping claims. It is a complex, human institution operating under significant pressures, embodying noble aspirations while simultaneously exhibiting profound flaws.

The presumption of innocence remains a vital legal and moral principle, essential for safeguarding individual liberty against state power. However, its practical effectiveness is constantly challenged by pretrial procedures, pervasive cognitive biases among all actors (investigators, lawyers, judges, jurors), the influence of public opinion and media narratives, and inadequate resources, particularly for indigent defense.

Manipulation by guilty parties, employing tactics designed to deny, attack, shift blame, and undermine the victim's reality (DARVO, gaslighting), is a real possibility. These tactics can exploit the system's inherent vulnerabilities – the fallibility of evidence, the potential for bias, and procedural loopholes – to achieve unjust outcomes. Furthermore, instances of official misconduct demonstrate that manipulation and injustice can originate from within the system itself.

Addressing the serious issues raised requires not an abandonment of the pursuit of justice, but a commitment to systemic reform. This involves:

Enhancing Accuracy: Implementing evidence-based practices to minimize errors, such as reformed eyewitness identification procedures, rigorous validation and cautious application of forensic science, and mandatory recording of interrogations.

Mitigating Bias: Promoting awareness of cognitive biases and manipulation tactics among all legal professionals through training; developing procedures designed to counteract biases (e.g., blind sequential lineups, contextual information management for forensic analysts); and actively addressing systemic racial disparities through policy changes and data collection.

Ensuring Adequate Defense: Providing sufficient funding and resources for public defenders and court-appointed counsel to ensure effective representation for all defendants, particularly the indigent.

Accountability and Transparency: Strengthening mechanisms for holding police and prosecutors accountable for misconduct, including robust internal affairs processes, independent oversight, and potentially revisiting immunity doctrines. Supporting and expanding the work of Conviction Integrity Units. Increasing transparency in plea bargaining and sentencing.

Victim Support: Ensuring victims are treated with respect and provided with appropriate support, while guarding against victim-blaming narratives influencing legal outcomes.

The path forward lies in acknowledging the validity of the concerns about injustice and manipulation, while rejecting unworkable solutions and focusing instead on the difficult but necessary work of reforming the criminal legal system to better align its practices with its foundational ideals of fairness and reliability. The struggle to ensure that the guilty are held accountable while the innocent are protected remains a central challenge for any society committed to justice.

Comments